Awad and Muntaha

There is an epidemic of weddings in Taanayel Camp, a ramshackle site of about 50 Syrian refugee families in Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley. They say that they’ve had about five marriages in as many weeks and celebrated about 100 since the camp began life a year and a half ago.

Central Bekaa is dotted with 50 or so settlements like this one, with patched up tents, streams clogged by rubbish, dust, heat, children and nothing to do but dream of one day going home.

Most of the people here are from villages outside Aleppo. Everyone has a story to tell of living through hunger and bombs, seeing friends and relatives killed and fleeing to an uncertain future as one of Lebanon’s one million Syrian refugees.

The most recent newly-weds are Awad and Muntaha, married a week or so ago. “The second or third time I saw Muntaha, my heart started beating for her,” said Awad.

Awad (R), 15, and his new bride Muntaha, 14, poses in a Syrian refugees camp on June 17, 2014 in the Lebanese village of Zahle in the Bekaa valley. They just got married few weeks ago in the camp. Matthieu Alexandre/Caritas

Friends and neighbours rallied around to throw a small celebration. “I was happy my son was getting married,” said Awad’s father. “It was sad that it was here in this camp, but it’s a sign of hope.”

Awad is 15, Muntaha is 14. They have both been out of school for three years: the education system was an early casualty of the war in Syria. The men in the camp say that marriage as young as this is normal.

“In the Islamic tradition, you are not a complete person until you are married,” says Awad’s father, who himself was married at 14, has three wives and has seen three of his daughters married, all at around 14-years-old too.

The law in Syria sets the minimum age of marriage at 17 for boys and 16 for girls. However, religious leaders are allowed to approve informal marriages at the age of 13 for girls and 16 for boys.

UN research into early marriage of Syrian refugees shows over half of women were married before 18. Many aid workers say that early marriages are increasing as parents believe their daughters will be better protected from rape if they have a husband.

“Life here in the camps isn’t stable. We have had to flee. We have no work, no economic security. Seeing Awad marry makes things feel more secure,” said his father.

The couple plan to have children when they “can touch Syrian soil again.” Pregnancy in girls as young as Muntaha can be dangerous or lead to complications in latter pregnancies.

Not everyone is convinced by the wisdom of their union. “They’re just kids,” said Aziz, only 18-years-old himself and getting married next week.

Amar

When Caritas social worker Laurette Challita first met Amar during a home visit to Syrian refugees in northern Lebanon it was “creepy”.

The 18-year-old girl had a thin, expressionless face, stark white underneath her black headscarf. Amar’s gaze didn’t move. When asked if she needed help, she began repeating the word “Inshallah”.

Amar wouldn’t interact with her family and her father had to force her to eat. Whenever a plane flew over, she would hide in the bathroom.

Amar, 18, a newly arrived Syrian refugee woman victim of a trauma, poses on June 19, 2014 at Caritas Migrant Center in Dahr El Ain, near Tripoli. Amar is catatonic and didn’t speak for the last 6 months. The background shows a drawing made by 100 women for the Women’s Day on March 8, 2014. Credit: Matthieu Alexandre/Caritas

Laurette Challita has had ten years of experience helping the victims of the conflicts in Iraq and Syria. This was the worst case of trauma the seasoned social worker had ever seen. Gradually she started to put the story together.

Amar had been married at 14 to her husband, who was 25-years-old. It was an arranged marriage, but her father said that the couple fell in love. They had a baby son two years ago.

Then the civil war came to Aleppo. Her parents fled to Lebanon, leaving their daughter alone with her husband’s family. A bomb hit a car Amar was travelling in. She survived but began to behave strangely afterwards.

Her mother-in-law didn’t understand that it was a mental illness and began to abuse her, calling her ‘possessed’. The mother-in-law pushed for her son to get married again. When he got engaged, the mother-in-law dragged Amar to the party.

When her condition deteriorated, Amar was sent to live with her parents who by now were refugees in Lebanon. Being separated from her baby son caused the young woman’s mind to lockdown.

“I was shocked at what she’d become,” said Ahmed, her father. “Amar means ‘moon’ in Arabic. The Amar I knew shone like the moon. She was so radiant, so caring and so clever.”

Amar was referred to a Caritas psychologist, Caroline Ghosn. “She was catatonic and had developed multiple personalities as protection from what she’d gone through,” said the doctor.

Amar with Caritas psychologist, Caroline Ghosn during a therapy session. Credit: Matthieu Alexandre/Caritas

Amar’s therapy has been slow going, but one day she threw and caught a ball. “It was a breakthrough,” said her psychologist.

Her father doesn’t blame the husband or his family, only the war. The husband, he said, has broken off his engagement and asked for Amar back. For now, she is staying put.

“It was a mistake for them to get married so young,” said the father. “At that age, how can you cope with something like this.”

Fatima Ali

Sitting in the corridor of a Caritas medical centre in Beirut, Fatima Ali says she has seen enough suffering to last three life times.

The 34-year-old mother of five is a refugee from Homs, a city devastated in Syria’s three year long civil war. “There was nothing there but the bombs,” she said.

After her family fled to Lebanon in 2011, her 16-year-old son Mohammed started to get sick. He was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s disease, a type of cancer.

Treatment for cancer is expensive and the demands put on Lebanon’s healthcare system by one million refugees are large. Only a quarter of the UN appeal for the Syrian crisis is funded.

Fatima Ali(R), waiting for her turn at St Michel Medico-Social Center, supported by Caritas, on June 20, 2014 at Sed El Baouchrieh in Beirut. Credit: Matthieu Alexandre/Caritas

“They said that you could treat 200 people for the cost of treating my son,” said Fatima. “I asked them how you can treat somebody who has a cold and not care for a child with cancer.”

By borrowing money, she was able to get Mohammed the care he needed. But at the same time, things had begun to unravel at home.

Fatima was from a farming community in Syria. She had married young, at 14. “I wanted to stay at school. I had won awards at Mathematics,” she said. “My education finished when I got married.”

Then as a refugee in Lebanon, her husband became very violent. “He’d hit me so hard I would get fractures,” she said. The children, aged 16 to 8, were forced to work long hours in the fields, even Mohammed. The cancer returned.

“We fled when my husband wanted to marry my 13-year- old daughter to a 47-year-old Lebanese man,” said Fatima. The man was offering $3000. He already had three wives.

Caritas runs shelters for abused women and they’ve taken Fatima and her family into one. Caritas provided her with legal aid and she was able to get a divorce and custody of the children.

Now her focus is on finding a permanent place to stay, on getting her children into a school and getting Mohammed treatment.

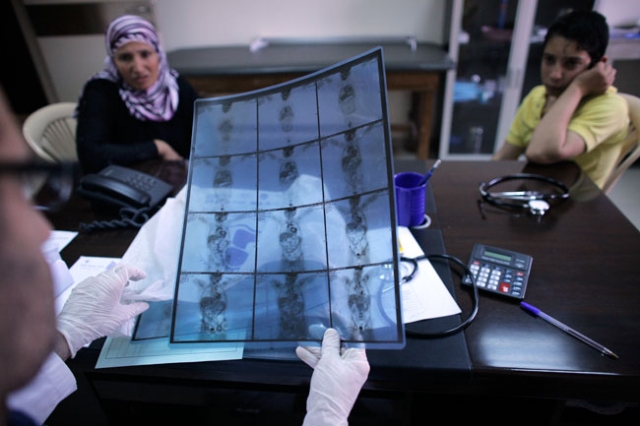

Doctor Rouchdi El Hajj (L), pediatrician, looks at X-ray of Mohammed (R) suffering from a cancer at St Michel Medico-Social Center, supported by Caritas, on June 20, 2014 at Sed El Baouchrieh in Beirut. Credit: Matthieu Alexandre/Caritas

The doctors at the Caritas clinic believe if he gets the help he needs, his future is positive. They aren’t equipped to deal with cancer at the clinic, so are trying to find him help elsewhere.

“I’ll sit outside the UN if I have too,” said Fatima. “You must be strong to be a mother. I wasn’t strong before, but I am now.”